Welcome to Creative\\Proofing, a space for hopeful, creative people learning to live wisely by asking questions about the good life: what it is, how to design our own, and how to live it well.

This newsletter is built on the hope of reciprocal generosity: I want to share what I find beautiful and meaningful, and I'd love for you to do the same. If you're inspired by anything I share, it would mean so much if you shared it with others, subscribed, dropped me a line and let me know, or paid according to the value it has for you. No matter what, I hope we can create and learn together.

Reflection

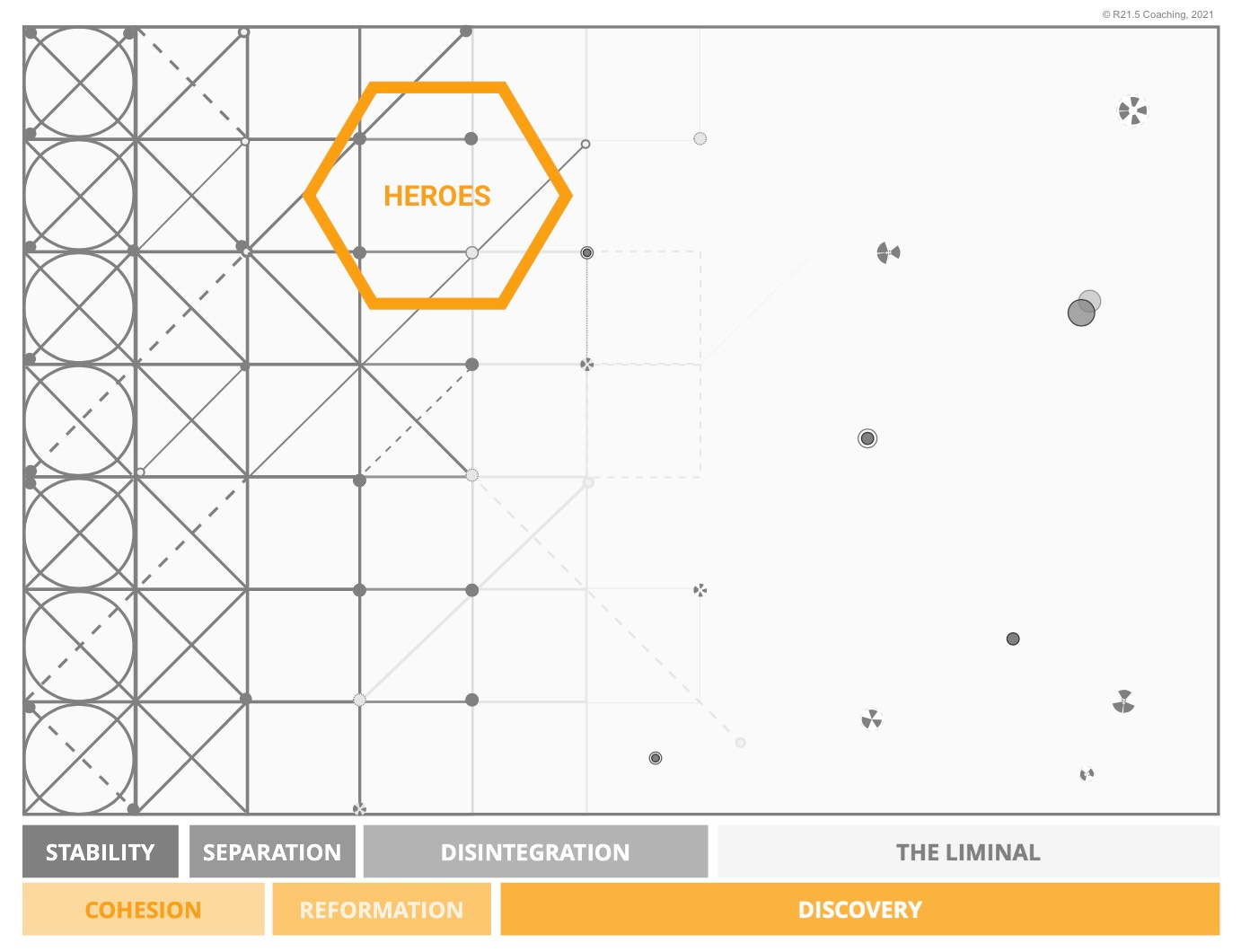

With the development of The Liminal Space framework and visual, and discerning how we might move about within it, I'm looking back at significant periods of my life, reflecting on where I've been, where I've traveled to, and what I carry with me still.

In the first half of this essay, my life fell apart: before diagnosis, before cancer, before surgery, before anything approaching a recovery. I feel lucky: my father had the same cancer 16 years before, and I knew very well what to expect, what to dread, what to hope for. Still, there's always a sense of white-knuckling it through every doctor's appointment, every encouragement from well-meaning acquaintances, every deep midnight waking into shivering fear.

Such moments stain your life ever after: how you choose to connect subsequent moments and events, the meaning you discover or discern in those linkages... It all reforms into shapes and structures that appear familiar, yet for me clarified a persistent longing for some hitherto unrealized cohesion, a wholeness that the entire episode revealed as lacking in my life before. In this second half of The Other Side of Normal, I explore how I began to reform into the familiar and yet strange self that is me on this journey.

What I know these days is that there's no perfectly formed future waiting for me on the "other side." There's only the next step I take now.

Let's be hopeful, creative, and wise — together.

Shalom,

Megan.

Read Part I

The Other Side of Normal, Pt. 2

Originally published at The Other Journal, Oct. 18, 2012

Did I mention this all happened during Lent? I found it poignant, in church on Ash Wednesday, to have ashes smudged across my forehead when I carried them in my body. We prayed the day’s liturgy over our ashes.

“Remember you are dust, and to dust you shall return.”

Did you think I would forget?

“One day my life on earth will end; the limits on my years are set, though I know not the day or hour. Shall I be ready to go to meet you?”

Is this the limit to my years? Meeting you here chokes me.

“Let this holy season be a time of grace for me and all this world.”

I do not know how to ask you for anything, let alone for grace. I feel like a beggar who cannot beg.

Lewis again: “The cross comes before the crown.”1 Suffering before joy. I strove to play the hero, to wear beautiful armor. In that pre-op room, holding a ridiculous hospital gown, waiting to have my throat cut open, the armor fell apart. It revealed the child beneath, white-blind with terror, trembling, caught between desire and necessity.

I do not want to. I cannot. I must.

When you wander a garden at night, you carry hope like a flashlight. You anticipate finding treasures beneath the rocks or fairies fluttering about or at least a talking beaver. But when hope is a crown of thorns, that same garden becomes a place on a map over which ancient sailors used to write, “Here be dragons.” Shadows dance, gates clang shut behind you, and you wonder if you will make it through the danger intact. Hope beckons us; hope drives us: always onward.

Christ found no consolation in a life after death because that very life compelled him to die. No one else could take the cup God2 held out to him. Could I find consolation in his life? Could I find strength in his sufferings? I cannot let go of the cup given to me until I drink the whole draught. I will not let you go unless you bless me.

My mother waited with me in pre-op. In the moment when I could only perceive my terror, she held me, gave whatever mothers give their children in such moments, kept nothing back for herself. But she could not stay. I often consider Christ’s disciples sleeping while he prayed and wrestled in Gethsemane. They wanted to wait up with him. They wanted to walk beside him and bear the weight. Yet I doubt the evening could have gone any other way. Only we can lift the cup of suffering that is poured out for each of us. No other feet can carry us through the garden but our own. Sometimes Love mediates himself through others. Sometimes Love forces us to hope in the dark—alone, with a cup full of thorns.

I remember clearly the nurses wheeling me through double doors to surgery, and I remember waking up in recovery hours later, my jaw spasming uncontrollably. Without my glasses or hearing aid, resurrection started off blurry and quiet. I learned anew the blessing of strangers’ kindnesses, the comfort of unknown hands smoothing hair off my brow. The surgeon came by to tell me of the surgery’s success. I already knew. Does God give us such intuitive graces? Potential became a good word again.

Ding dong, Fredi’s dead! Yet the Munchkins misled me on this point. The Cancerous Bastard did not just shrivel up and poof! away. His exodus, lobbing one final “I’ll get you, my pretty,” left me chafing at my body’s weakness and reduced ability to respond when I asked it to perform. Several weeks of doctors’ visits, prescription and supplement changes, outings cut short by massive energy drainage—I failed to find the normal in this. I didn’t want to. I began to understand the rest of Rilke’s advice: living the questions now means living “along some distant day into the answer.”3 Since childhood I have asked, “Shall I be ready to go to meet you?” Shall I ride out to face the day’s dragon on the path ahead of me? Each day I live into the answer.

In the beginning, the diagnosis of cancer made a difference in my thinking, but otherwise, I could go on living as I had before. I kept hoping I wouldn’t have to have the surgery, because that would make the cancer real. But Fredi existed, and I did, and now I know: normal changes. I have a scar: a short parenthesis at the base of my neck, Fredi’s exit wound, his parting shot. I am not as I once was. My body lacks something it needs, and all the beneficial medicines in the world can’t fully replace the organ removed. I disliked my scar in the beginning and delighted as time steadily weathered it away. But three years into the journey, it’s become my new normal.

All courage begins in hope, even if it’s only a mustard seed’s worth. I once feared the path to courage because I could only see death in it. But St. John reminds us: “Beloved, we are God’s children now, and what we will be has not yet appeared; but we know that when he appears we shall be like him, because we shall see him as he is” (1 John 3:2 ESV). As I followed the path past watchful dragons, I began to glimpse the hero who pulled Finn MacCool and Beowulf and Skírnir up into himself and shifted the path beyond death into life. The thing about heroes is that you’ll follow them anywhere, because the best ones always show you who you could be. I discovered in the great Hero all that I loved best in those mythical heroes—bravery, strength, fidelity, love—and I discovered that, in following him, I was becoming not different but myself.

We are all of us God’s children, and grace-full fearlessness is better than a faint heart in facing this life he’s given. I think a lot about redemption at the end of time—mostly about the redemption of my own broken earthwork body. I would prefer to exist as disembodied spirit and often fight to enjoy this intertwined self of mine. He created us good, though. Someday, our entire self will come alive in the new heaven and new earth, gloriously familiar and yet strange, on the other side of normal. You and I will at last become all we have longed in this life to be, and our incomplete prayers and half-told tales will at last find the Word that makes them whole.

Lewis, The Weight of Glory (San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 2001), 45.

A Quick Note: I work from within the Christian tradition, and understand the Divine as the Trinity of father, son, holy spirit. That said, I know we all have different ways of understanding God and the Divine, so if you wish to insert [Other] when I use that phrase, please feel free to do so.

Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet, 35.