Greetings!

Welcome to 2025, my beloved conglomerations of vibrating atoms!

Let’s get to it, shall we?

Birds do it.

Bees do it.

Even educated fleas do it.

Let’s do it… Let’s do it…

Let’s…communicate!

Not where you thought that was going, is it?1

What’s It?

Today we’re taking a look at human communication: what it is, how it’s studied, and the theories that can help us analyze and improve our own practice. Let’s take this as the start of an occasional series of essays that focus on specific communication theories, and use them to explore and analyze other aspects of human life.

But first… What is communication?

It’s something we do all the time, everyday.

People, animals, plants, atoms…when you get down to it, the entire universe communicates in one way or another.

We use words, noises, written symbols, analog and digital technologies, body language. Creatures use sounds and their environment. Atoms vibrate.

Communication is so ubiquitous, we probably don’t even realize how much we signal in every conscious second of every day. Not to mention how much we receive.

It’s easy to overlook how pervasive, important, and complex the process and fact of human communication is, because it intertwines with all of human life so completely. It’s as much a part of our existence as the air we breathe.

The Purpose of Communication

But have you ever paused to consider what communication is for?

We use it in different ways, depending on what we want to achieve. Though I describe these as distinct modes, we usually activate multiple modes in any given interaction. Like motives, we never have just one.

There’s functional or practical communication, which we use when we want to get things done or transfer information, usually in the form of statements or orders.

There’s exploratory communication, which we engage in the process of learning or discovery, usually in the form of questions or wonderings. We may also engage this type of communication when we’re trying to contextualize or comprehend our experiences.

There’s invitational communication, in which we appeal to or request something of others, such as seeking help or extending hospitality.

There’s persuasive communication, traditionally called rhetoric, that we practice when we’re arguing a point, soliciting agreement, or selling something. Sometimes this mode of communication can tip into propaganda.

And there’s relational communication, which includes all of the above modes, but primarily seeks connection with others as its primary purpose.

Indeed, I believe that the deepest longing, the purest or truest purpose of human communication is to enable us to know and be known by others, by ourselves, by the divine.

When we share a favorite song, recommend a book, converse with someone for hours, or ask a question out of genuine curiosity, we want to be seen and recognized for who we are, to be invited into relationship with another person. We offer such nuggets of communication in our effort, our hope to create connection.

In the end, we seek to offer and receive love, which, as Rainer Marie Rilke once wrote: “consists of this: two solitudes that meet, protect and greet each other.” Whether romantic, familial, or platonic love, we all feel that sense of being solitudes seeking to cross that boundary and find welcome with another.

With all of these purposes and their myriad expressions, and the desire for knowing and being known, we begin to see how communication can quickly become very complex, and often very frustrating.

Studying Communication

The process and experience of human communication has always fascinated me.

I’ve often wondered if growing up and living with severe hearing impairment has fostered this. Since I cannot rely upon a key means of receiving verbal communication the way most of us do, nonverbal and written communication, and my ability to interpret any signals I receive, becomes incredibly important.

When I decided to study for my master’s in communication, what I learned in those studies only reinforced what I’d long intuited: that communication is the organizing principle of human life. Without it, who would we be?

Communication theorist Robert T. Craig observes that communication “is the primary process by which human life is experienced; communication constitutes reality.” In studying communication processes and theories, we can at least become aware of how we practice communication. Such study provides us with useful tools to help us understand how we individually and collectively define and discuss our experiences, and thus share our realities.

In his 1999 article “Communication Theory as a Field,” Craig proposes seven traditions that each have their own way of understanding human communication:

Rhetorical views communication as the practical art of discourse.

Semiotic views communication as the mediation by signs.

Phenomenological sees communication as the experience of dialogue with others.

Cybernetic describes communication as the flow of information in interdependent, self-regulating systems.

Socio-psychological communication is the interaction of individuals.

Sociocultural communication is the creation and reproduction of the social order.

Critical communication is the process in which all assumptions can be challenged.

If some of these sound familiar to you from sociology, anthropology, or psychology classes, you are not wrong. There’s a lot of cross-pollination going on.

The best way to understand the multiplicity of traditions and theories is, as with any field of study, to allow these “concept families” to reveal, define, and illuminate for us different aspects of how we practice communication.

Symbolic Interactionism

Of course, everyone has their favorite theory or theories, and today I’m sharing symbolic interactionism.

Why symbolic interactionism?

Because I like it.

But also, this and similar theories resonate so strongly for me because I value interconnectedness and connection so highly. When I visualize the world, I frequently see it as an ecosystem: a dynamic, responsive, connected web of relationships. And the sociocultural and cybernetic traditions offer theories that most closely align with that image.

Like its sister theories of coordinated management of meaning, impression management, and sense-making, symbolic interactionism concerns itself with meaning and action: what matters and why, and what we do about that.

The History of SI

Symbolic Interactionism (SI) is part of the sociocultural family of communication theories, which emphasizes the patterns and processes of interaction between people and within the self. Interaction is defined as the process and site in which meanings, roles, rules, and cultural values are worked out. In this tradition, all of our concepts, categories, and structures are socially created in dialogue and collaboration with others.2

Social psychologist George Herbert Mead is considered the founding thinker of SI, though his student and colleague Herbert Blumer is the one who named the theory and did the most to interpret and share Mead’s thought. Mead primarily focused on how the individual self develops through interactions with others: how do we come to agree on and share meanings, and then act on those meanings? How do we construct a shared reality with others? In this view, we move from the individual to the collective by recognizing that society is the accumulation of repeated, regular interactions between individuals that negotiate meanings and actions.

This “social constructionist” perspective helps us see how we develop our sense of self and identity in relationship with others. While every interaction helps create, challenge, or reinforce our self-concept, it’s the social interaction with orientational others who are especially important or influential in our lives.3 These orientational others provide us with “general vocabulary, central concepts, and categories that come to define our realities.”4

The Meaning of Meanings

Symbolic Interactionism is understood as the social construction of meaning. It’s primarily concerned with symbols: how we become aware of and name them, and how we anticipate others will act toward those symbols. That anticipation is the site of a process of role-taking and interpretation: what do I think or expect this person to do? How will this person respond? How will I respond to that?

There are three main principles in SI:

We act based on meanings.

example: if we have a high value of honesty, we will always act so that we tell the truth.

Meaning arises from interaction (dialogue, collaboration, and negotiation).

example: others in our social group also act toward the value of honesty by always telling the truth.

We modify meanings through interpretation, so that we can deal with the situations that we encounter.

example: what happens when we encounter individuals or groups who frequently lie?

Here, I should take a moment to address meaning, or at least how I understand meaning.

When we encounter new experiences, whether they’re exciting, welcome, unwelcome, frightening, we look to our past to help us make sense of this new thing. We try to figure out how this new situation fits in with what we already know and do, by taking old and new moments and putting them together in a new way.

It’s in that conversation (or interaction) that you have with yourself in the space between those moments–the story that you tell about how those moments fit together–where you make meaning in your life. It’s the story that you tell about who you are and how you got to here.

Meaning comes from a long string of moments THEN that shape who we are NOW.

Symbolic Interactionism, In More Detail

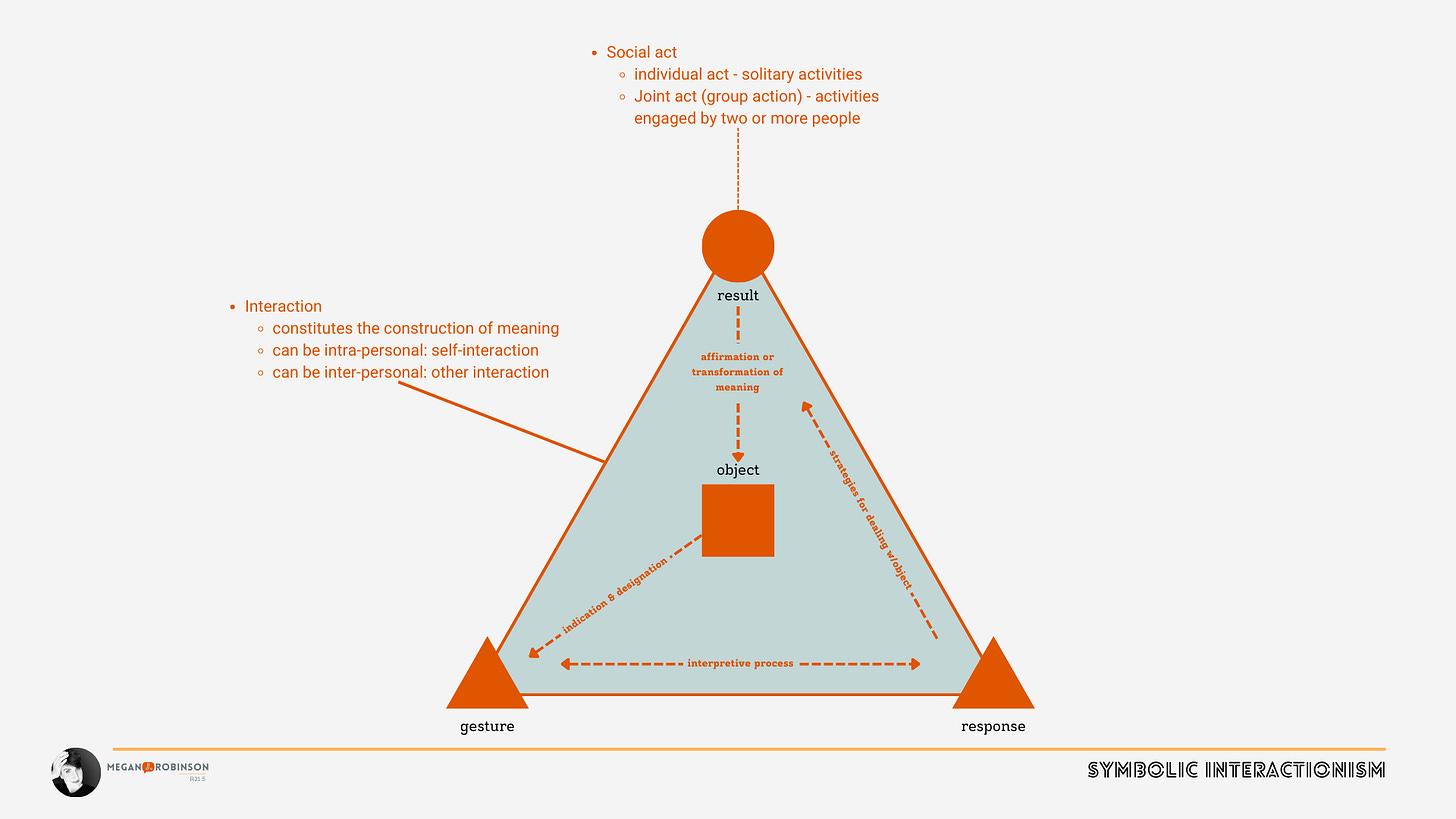

In SI, we construct meaning through our interactions. The interaction is always triadic, comprised of a gesture, a response, and a social act. No one “leg” of this triad conveys the meaning; rather, it’s the movement between them that constructs and establishes the field of meaning.

At the center of this field lies the object, which can be anything in our environment: physical, concrete things, such as chairs, books, food; social things, such students, family members, friends; and abstract things, such as moral principles, philosophical theories, or concepts of justice, compassion, grief, or love.

When an object moves from the background to the foreground of our awareness, we indicate and name it to ourselves. We are now aware of it and must decide what it means to us.

This moment of awareness, of naming the object is the gesture, the first leg of our interaction. A gesture can be nonsymbolic or symbolic. Nonsymbolic gestures are direct and require no interpretation: a dog barks, water falls from the sky, you wake up. Symbolic gestures, however, are indirect, and can only come from human beings: you tell your spouse the dog is barking, that water is coming through the ceiling, that you just had to get out of bed today. Symbolic gestures, i.e., symbols, require us to remember shared meanings, then anticipate and interpret likely responses, which is the second leg of our interaction.

A wedding ring is both a nonsymbolic gesture in that it’s simply a piece of metal, but also a symbolic gesture in that it stands for marriage, family, fidelity, legal and sacred contracts, and so on. But depending on your own personal and social history of interactions with “wedding rings,” you may interpret a marriage proposal as a cage, a burden, or an outdated social contract.

Our identities are also objects, and the meaning of our identity–our self-concept–lies in how we act in response to the identity we believe we have or that we think others expect us to have.5

So we have the gesture and the response, which are linked through the interpretive process.6 The final leg of our triad is the social act, or the action. This can be individual (something we do on our own) or joint (something we do in collaboration and alignment with others). This action either affirms or transforms the meaning of the initial object, which takes its place in our history of meanings.

We take action in response to situations; put another way, situations are the pre-condition for taking action. Whereas other perspectives see people responding to social structures or “the culture,” SI posits that we only ever act toward situations: noticing hunger, seeking companionship, organizing a group, etc.

Our personal lives, our communities, and our societies arise from the accretion of social actions and coordinated behaviors that manifest shared meanings developed over time.

The key terms we need to keep in mind for symbolic interactionism are: identity formation; (triadic) social interaction; meaning; and, symbols.

We develop our identities by interacting with others in negotiating and reinforcing the meaning of symbols, which are objects (concepts, language, behaviors, things) that carry specific meanings and help us communicate with each other.

There is, of course, more detail to the theory of symbolic interactionism, but I don’t want to risk (further) glazed eyes and checked-out minds. I hope that this introduction to SI provides a starting point for us to begin thinking about our process and practice of communication.

Some Reflections

I recently encountered the philosophical or theological (depending on how you squint at it) stance of personalism, which emphasizes the inherent dignity and worth of human persons, which cannot be reduced to means. We are ends and goods in ourselves, and cannot be used, extracted, or otherwise exploited.7 It seems to me that personalism and symbolic interactionism complement each other well, especially if we are concerned with becoming fully-flourishing persons.

One of the things I really appreciate about SI is that it recognizes our individual agency while also acknowledging that we don’t exist in a vacuum. We owe a great deal of who we are to our social environments.

I grew up in a religious tradition that emphasized personal agency (especially with regard to salvation), almost to the point of monomania. To point toward any other factors that shifted or shared responsibility was akin to “the devil made me do it,” and this was Not Allowed. I have never quite shaken the sense that individual responsibility and ownership matter a great deal for personal formation. That said, I’ve come to understand how systemic forces, though initiated by individuals in processes much like that described here, can gather momentum and acquire a self-reinforcing power of their own.

A phrase I frequently mutter to myself these days comes from media theorist Marshall McLuhan: “Nothing is inevitable, so long as there is a willingness to contemplate.” We run our lives and our social systems on auto-pilot most days (which is not a bad thing!), but when we take a step back to look at something as omnipresent and automatic as our communication… We begin to understand why so much of contemporary society feels “inevitable” due to the difficulty, complexity, and importance of a process we take for granted.

But I think that “communication awareness” may be one of those practices where small investments in negotiating new meanings return major dividends in creating different futures for all of us.

I’d love to hear what insights or observations this initial essay on human communication prompts for you. Drop a comment and let me know!

And don’t forget to check out the first episode of People Watching on Tuesday, January 14. I’m talking with Dr. Sandra Glahn, journalist, author, and professor of Media Arts and Worship at Dallas Theological Seminary. It’s so good.

Let’s become hopeful, creative, and wise–together.

Shalom,

What else?

Looking for more resources to help with your personal formation journey? Get your free guide!

My practice-based workshops help you practice commitment care or map your role models so you can become the person you were created to be. Great for small teams and student groups!

You can learn more about this newsletter and my work on the About page.

Have a question? Ask me anything.

One more thing…

Want to help me continue sharing free stuff? Buy me a book!

Littlejohn, Stephen W.; Foss, Karen A. Theories of Human Communication (p. 55)

Littlejohn, Stephen W.; Foss, Karen A. Theories of Human Communication (p. 100, 116)

I’m looking forward to thinking more about how role models are, in this theory, an object with which we interact to make meaning, and thus, engage our formation.

Which I don’t feel is fully discussed or explained in SI (or possibly even understood by this essayist), so we’ll probably bring in other theories to explore that more in the future.

A perspective which will be challenged in the first read of the year, Shoshana Zuboff’s The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. Stay tuned!